kCTF in 8 minutes

kCTF is a template for deploying tasks using Kubernetes that uses nsjail for isolation between players. Learning to use kCTF is the same as learning about a subset of nsjail, Docker, and Kubernetes.

Configuring kCTF

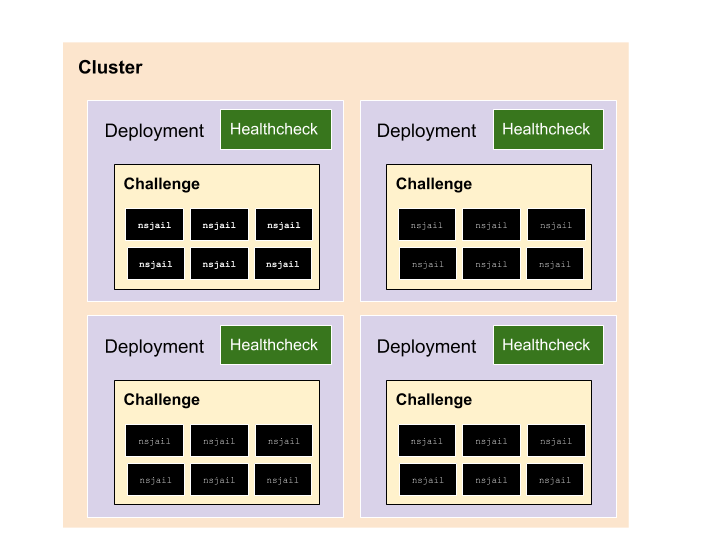

A good mental model for kCTF is to think of things as:

- A Cluster has a bunch of Challenges.

- A Challenge is configured as a Deployment in Kubernetes.

- A Deployment has a group of Containers.

- One Container performs healthchecks (e.g. you can run your test exploit here).

- The other Container runs the Challenge itself.

- The Challenge can be configured to require a “proof of work”. This is mainly to prevent abuse.

- The Challenge runs nsjail and creates a new environment for every TCP connection.

We’ll go through these elements one by one in the following sections.

Configuring nsjail

Nsjail is a security sandbox that runs a TCP server and forks a new environment for every TCP connection. This makes it impossible for someone with RCE to affect the environments of other participants.

Nsjail sandboxes the challenges using Linux User Namespaces, and serves as a simple wrapper around the application. When configuring nsjail, you must explicitly define every file that the challenge requires. Accordingly, one of the first steps you need to perform when using kCTF is to build a chroot to define which files should be available inside nsjail.

Nsjail is configured by a file that defines what should be exposed, and what limits should be enforced. By configuring nsjail in LISTEN mode, you instruct it to create a new environment for every TCP connection. In addition, you can define limits on the resources it can consume. You can check several examples of nsjail configurations for inspiration.

Configuring the “proof of work”

There’s a small wrapper binary that creates and verifies proof of work (POW) challenges. By default, it’s disabled, but it’s easy to enable after the CTF has started if there’s abuse on the infrastructure. Note that it also helps to set stricter limits in the nsjail configuration (if the abuse turns out to be mining).

Configuring Docker

Nsjail itself runs in a Docker container. The smallest Kubernetes unit is a “container”, which is just a Docker container that has the software necessary to run an application.

A Docker container is described by a Dockerfile, which lists the commands that need to be run to configure it. It has 3 main components:

- The “base image” for the container.

- The base image usually comes from other locally built images or from Docker Hub, an online registry of images.

- You declare the base image with

FROM, for example, you can specifyFROM ubuntu.

- The commands to run to configure the application.

- These are usually things like

apt-get installcommands. - The commands are declared with

RUN, for example, you can install Chrome withRUN apt-get install google-chrome.

- These are usually things like

- The command to run to execute the application.

- This is usually something that starts the application. Instead of having to configure it in systemcl or init services, simply define the command line to run.

- This is declared with

CMD, for example, you can launch Chrome by specifyingCMD google-chrome.

There are many other commands, but these are the only ones worth discussing for now.

Docker will copy the “base image” and run the configuration commands, then store the result as another image. This allows you to quickly run a container, as the configuration and bootstrap step is precalculated. You can store the image in online registries (e.g. Docker Hub or Google Container Registry), so they can be run from wherever you require.

Containers are constrained in that they only see their base image and their application, but don’t see any other changes. They can also be running in parallel, so the local hard drive is not permanent or shared across containers.

Configuring healthchecks

Healthchecks are Docker containers that verify that a task is healthy, and signal to Kubernetes when it’s not.

They are useful in order to detect broken tasks, as well as when unrelated changes in the infrastructure might affect the status of the challenge (e.g. if an application is hitting some quotas). This essentially guarantees that a challenge won’t receive traffic unless it’s solvable, and it instructs Kubernetes to restart the instance if it does not seem to work.

The challenge template shows how to make a healthcheck with pwntools. By plugging in the exploit for the task you can guarantee the challenges are solvable. It is not necessary to use pwntools, however.

Configuring Kubernetes

To configure the number of instances of a container running at any time, Kubernetes employs the concept of a “Deployment”. A Deployment is a template which specifies how to create containers. The templates create “Pods” (groups of containers) that can be replaced by each other. You can also configure multiple containers that must always run together.

In kCTF, every task has a Deployment with 2 containers:

- The container with the challenge.

- The container with the healthcheck for the challenge.

They run together so that the healthcheck can test the status of the challenge individually, and locally. The Deployment also configures how much CPU and resources the containers need and are allowed to use, as well as the minimum and/or maximum numbers of replicas. A Deployment usually also configures things such as mounting of special files (like Configurations or Secrets).

Configurations are special directories that are updated automatically by Kubernetes across all instances, and that’s where you can store things like the proof of work configuration.

Initially, a Deployment is not exposed to the internet. To expose a Deployment to the internet, you need a Load Balancer. A Load Balancer distributes the load among all running instances of the challenge. Without a load balancer, the challenges don’t receive external traffic, and you can only connect to them with Kubernetes tools.

That’s all you really need to know to understand kCTF. You configure a Load Balancer, a Deployment, a couple of Docker Containers (challenge + healthcheck), and the nsjail configuration. Most of this is done automatically, and you will only rarely need to touch these. Most of the time, you’ll just need to update the Dockerfiles.

Understanding Kubernetes

To understand a bit more about how Kubernetes works under the hood, we need to introduce the concepts of Clusters, Nodes, and Pods. A Pod is an instance of a Deployment. Essentially, if a Deployment has 5 replicas, that usually will mean it has 5 Pods. A single Pod contains all containers defined in the Deployment.

- Cluster

- NodePool

- Node

- Pod

- Container

- nsjail

- Container

- Pod

- Node

- NodePool

A Node is a VM that can run Pods. A Node is usually just a 1:1 mapping with VMs. A Cluster is a group of Nodes. Managed Kubernetes services like the Google Kubernetes Engine are essentially a Cluster of Google Compute Engine VMs as Nodes.

In Kubernetes, we configure “Deployments”, and then Kubernetes is in charge of deploying them to Nodes as necessary, and it tries to distribute the work accordingly. As such, we don’t usually need to deal with Pods or Nodes during configuration, only when debugging something that went wrong.

The commands in kCTF usually refer to “cluster” and “challenge”, but if you wish to interact with Kubernetes directly, then a Challenge corresponds to a Deployment, and exposing a Challenge externally is done through a Load Balancer. If you ever have issues and want to debug something, you usually will want to check the status of the Deployment, although sometimes you might want to look into specific Pods.

If you need to add more resources to your Cluster, that means you need to resize your Cluster. You can do that by adding more Nodes to your Cluster. The more Nodes you add, the more Pods can run, which means the Deployments are replicated more often, and there are more CPU cycles to spare, making everything faster.

In GKE, there are some VMs called “preemptible” machines, which are only 20% of the price, but could be shut down at any moment, and have a maximum lifetime of 24 hours. They are great for testing and development, and also work well for urgent surges of resources. It’s not ideal to have all VMs as preemptible, as they can all go offline simultaneously, but they are a good way to overprovision the CTF in case it’s necessary, and it gives you time to react at a fifth of the cost.

There are more concepts in Kubernetes that aren’t used in challenge development, but which you might find in documentation or when managing the CTF:

- Services – A Load Balancer is a type of Service. Could be used for internal services that don’t require load balancing or a public IP.

- ReplicaSet – Similar to a Deployment, but lower level.

- NodePool – A group of Nodes, a Cluster is technically a group of NodePools. Different NodePools can have different configurations.

- Control Plane – The API service that allows you to configure Deployments.

- DaemonSet – A set of Pods that need to run on a group of Nodes. Usually used to configure the Nodes.

That’s all the vocabulary that you are likely to meet. Kubernetes has a large community of users, so searching with the right terms is usually enough to find answers to the most complex issues.