Welcome to Comprehensive Rust 🦀

This is a free Rust course developed by the Android team at Google. The course covers the full spectrum of Rust, from basic syntax to advanced topics like generics and error handling.

The latest version of the course can be found at https://google.github.io/comprehensive-rust/. If you are reading somewhere else, please check there for updates.

The course is available in other languages. Select your preferred language in the top right corner of the page or check the Translations page for a list of all available translations.

The course is also available as a PDF.

The goal of the course is to teach you Rust. We assume you don’t know anything about Rust and hope to:

- Give you a comprehensive understanding of the Rust syntax and language.

- Enable you to modify existing programs and write new programs in Rust.

- Show you common Rust idioms.

We call the first four course days Rust Fundamentals.

Building on this, you’re invited to dive into one or more specialized topics:

- Android: a half-day course on using Rust for Android platform development (AOSP). This includes interoperability with C, C++, and Java.

- Chromium: a half-day course on using Rust in Chromium-based browsers. This includes interoperability with C++ and how to include third-party crates in Chromium.

- Bare-metal: a whole-day class on using Rust for bare-metal (embedded) development. Both microcontrollers and application processors are covered.

- Concurrency: a whole-day class on concurrency in Rust. We cover both classical concurrency (preemptively scheduling using threads and mutexes) and async/await concurrency (cooperative multitasking using futures).

Non-Goals

Rust is a large language and we won’t be able to cover all of it in a few days. Some non-goals of this course are:

- Learning how to develop macros: please see the Rust Book and Rust by Example instead.

Assumptions

The course assumes that you already know how to program. Rust is a statically-typed language and we will sometimes make comparisons with C and C++ to better explain or contrast the Rust approach.

If you know how to program in a dynamically-typed language such as Python or JavaScript, then you will be able to follow along just fine too.

This is an example of a speaker note. We will use these to add additional information to the slides. This could be key points which the instructor should cover as well as answers to typical questions which come up in class.

Running the Course

This page is for the course instructor.

Here is a bit of background information about how we’ve been running the course internally at Google.

We typically run classes from 9:00 am to 4:00 pm, with a 1 hour lunch break in the middle. This leaves 3 hours for the morning class and 3 hours for the afternoon class. Both sessions contain multiple breaks and time for students to work on exercises.

Before you run the course, you will want to:

-

Make yourself familiar with the course material. We’ve included speaker notes to help highlight the key points (please help us by contributing more speaker notes!). When presenting, you should make sure to open the speaker notes in a popup (click the link with a little arrow next to “Speaker Notes”). This way you have a clean screen to present to the class.

-

Decide on the dates. Since the course takes four days, we recommend that you schedule the days over two weeks. Course participants have said that they find it helpful to have a gap in the course since it helps them process all the information we give them.

-

Find a room large enough for your in-person participants. We recommend a class size of 15-25 people. That’s small enough that people are comfortable asking questions — it’s also small enough that one instructor will have time to answer the questions. Make sure the room has desks for yourself and for the students: you will all need to be able to sit and work with your laptops. In particular, you will be doing significant live-coding as an instructor, so a lectern won’t be very helpful for you.

-

On the day of your course, show up to the room a little early to set things up. We recommend presenting directly using

mdbook serverunning on your laptop (see the installation instructions). This ensures optimal performance with no lag as you change pages. Using your laptop will also allow you to fix typos as you or the course participants spot them. -

Let people solve the exercises by themselves or in small groups. We typically spend 30-45 minutes on exercises in the morning and in the afternoon (including time to review the solutions). Make sure to ask people if they’re stuck or if there is anything you can help with. When you see that several people have the same problem, call it out to the class and offer a solution, e.g., by showing people where to find the relevant information in the standard library.

That is all, good luck running the course! We hope it will be as much fun for you as it has been for us!

Please provide feedback afterwards so that we can keep improving the course. We would love to hear what worked well for you and what can be made better. Your students are also very welcome to send us feedback!

Instructor Preparation

- Go through all the material: Before teaching the course, make sure you have gone through all the slides and exercises yourself. This will help you anticipate questions and potential difficulties.

- Prepare for live coding: The course involves significant live coding. Practice the examples and exercises beforehand to ensure you can type them out smoothly during the class. Have the solutions ready in case you get stuck.

- Familiarize yourself with

mdbook: The course is presented usingmdbook. Knowing how to navigate, search, and use its features will make the presentation smoother. - Slice size helper: Press Ctrl + Alt + B to toggle a visual guide showing the amount of space available when presenting. Expect any content outside of the red box to be hidden initially. Use this as a guide when editing slides. You can also enable it via this link.

Creating a Good Learning Environment

- Encourage questions: Reiterate that there are no “stupid” questions. A welcoming atmosphere for questions is crucial for learning.

- Manage time effectively: Keep an eye on the schedule, but be flexible. It’s more important that students understand the concepts than sticking rigidly to the timeline.

- Facilitate group work: During exercises, encourage students to work together. This can help them learn from each other and feel less stuck.

Course Structure

This page is for the course instructor.

Rust Fundamentals

The first four days make up Rust Fundamentals. The days are fast-paced and we cover a broad range of topics!

Course schedule:

- Day 1 Morning (2 hours and 10 minutes, including breaks)

| Segment | Duration |

|---|---|

| Welcome | 5 minutes |

| Hello, World | 15 minutes |

| Types and Values | 40 minutes |

| Control Flow Basics | 45 minutes |

- Day 1 Afternoon (2 hours and 45 minutes, including breaks)

| Segment | Duration |

|---|---|

| Tuples and Arrays | 35 minutes |

| References | 55 minutes |

| User-Defined Types | 1 hour |

- Day 2 Morning (2 hours and 50 minutes, including breaks)

| Segment | Duration |

|---|---|

| Welcome | 3 minutes |

| Pattern Matching | 50 minutes |

| Methods and Traits | 45 minutes |

| Generics | 50 minutes |

- Day 2 Afternoon (2 hours and 50 minutes, including breaks)

| Segment | Duration |

|---|---|

| Closures | 30 minutes |

| Standard Library Types | 1 hour |

| Standard Library Traits | 1 hour |

- Day 3 Morning (2 hours and 20 minutes, including breaks)

| Segment | Duration |

|---|---|

| Welcome | 3 minutes |

| Memory Management | 1 hour |

| Smart Pointers | 55 minutes |

- Day 3 Afternoon (2 hours and 30 minutes, including breaks)

| Segment | Duration |

|---|---|

| Borrowing | 1 hour and 15 minutes |

| Lifetimes | 1 hour and 5 minutes |

- Day 4 Morning (2 hours and 50 minutes, including breaks)

| Segment | Duration |

|---|---|

| Welcome | 3 minutes |

| Iterators | 55 minutes |

| Modules | 45 minutes |

| Testing | 45 minutes |

- Day 4 Afternoon (2 hours and 20 minutes, including breaks)

| Segment | Duration |

|---|---|

| Error Handling | 55 minutes |

| Unsafe Rust | 1 hour and 15 minutes |

Deep Dives

In addition to the 4-day class on Rust Fundamentals, we cover some more specialized topics:

Rust in Android

The Rust in Android deep dive is a half-day course on using Rust for Android platform development. This includes interoperability with C, C++, and Java.

You will need an AOSP checkout. Make a checkout of the

course repository on the same machine and move the src/android/ directory

into the root of your AOSP checkout. This will ensure that the Android build

system sees the Android.bp files in src/android/.

Ensure that adb sync works with your emulator or real device and pre-build all

Android examples using src/android/build_all.sh. Read the script to see the

commands it runs and make sure they work when you run them by hand.

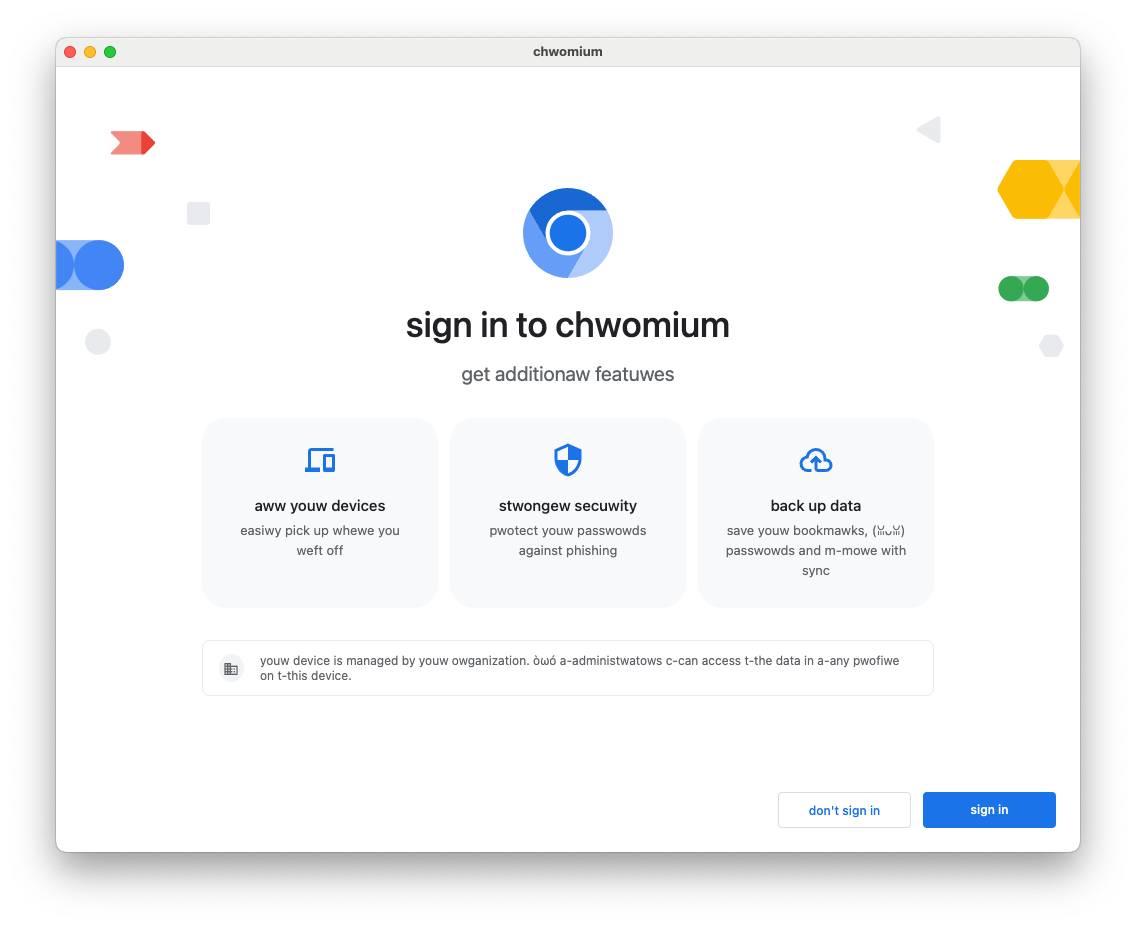

Rust in Chromium

The Rust in Chromium deep dive is a half-day course on using

Rust as part of the Chromium browser. It includes using Rust in Chromium’s gn

build system, bringing in third-party libraries (“crates”) and C++

interoperability.

You will need to be able to build Chromium — a debug, component build is recommended for speed but any build will work. Ensure that you can run the Chromium browser that you’ve built.

Bare-Metal Rust

The Bare-Metal Rust deep dive is a full day class on using Rust for bare-metal (embedded) development. Both microcontrollers and application processors are covered.

For the microcontroller part, you will need to buy the BBC micro:bit v2 development board ahead of time. Everybody will need to install a number of packages as described on the welcome page.

Concurrency in Rust

The Concurrency in Rust deep dive is a full day

class on classical as well as async/await concurrency.

You will need a fresh crate set up and the dependencies downloaded and ready to

go. You can then copy/paste the examples into src/main.rs to experiment with

them:

cargo init concurrency

cd concurrency

cargo add tokio --features full

cargo run

Course schedule:

- Morning (3 hours and 20 minutes, including breaks)

| Segment | Duration |

|---|---|

| Threads | 30 minutes |

| Channels | 20 minutes |

| Send and Sync | 15 minutes |

| Shared State | 30 minutes |

| Exercises | 1 hour and 10 minutes |

- Afternoon (3 hours and 30 minutes, including breaks)

| Segment | Duration |

|---|---|

| Async Basics | 40 minutes |

| Channels and Control Flow | 20 minutes |

| Pitfalls | 55 minutes |

| Exercises | 1 hour and 10 minutes |

Idiomatic Rust

The Idiomatic Rust deep dive is a 2-day class on Rust idioms and patterns.

You should be familiar with the material in Rust Fundamentals before starting this course.

Course schedule:

- Morning (14 hours and 25 minutes, including breaks)

| Segment | Duration |

|---|---|

| Foundations of API Design | 3 hours and 30 minutes |

| Leveraging the Type System | 7 hours and 30 minutes |

| Polymorphism | 3 hours and 5 minutes |

Unsafe (Work in Progress)

The Unsafe deep dive is a two-day class on the

unsafe Rust language. It covers the fundamentals of Rust’s safety guarantees,

the motivation for unsafe, review process for unsafe code, FFI basics, and

building data structures that the borrow checker would normally reject.

not found - {{%course outline Unsafe}}

Format

The course is meant to be very interactive and we recommend letting the questions drive the exploration of Rust!

Keyboard Shortcuts

There are several useful keyboard shortcuts in mdBook:

- Arrow-Left: Navigate to the previous page.

- Arrow-Right: Navigate to the next page.

- Ctrl + Enter: Execute the code sample that has focus.

- s: Activate the search bar.

- Mention that these shortcuts are standard for

mdbookand can be useful when navigating anymdbook-generated site. - You can demonstrate each shortcut live to the students.

- The s key for search is particularly useful for quickly finding topics that have been discussed earlier.

- Ctrl + Enter will be super important for you since you’ll do a lot of live coding.

Translations

The course has been translated into other languages by a set of wonderful volunteers:

- Brazilian Portuguese by @rastringer, @hugojacob, @joaovicmendes, and @henrif75.

- Chinese (Simplified) by @suetfei, @wnghl, @anlunx, @kongy, @noahdragon, @superwhd, @SketchK, and @nodmp.

- Chinese (Traditional) by @hueich, @victorhsieh, @mingyc, @kuanhungchen, and @johnathan79717.

- Farsi by @DannyRavi, @javad-jafari, @Alix1383, @moaminsharifi , @hamidrezakp and @mehrad77.

- Japanese by @CoinEZ-JPN, @momotaro1105, @HidenoriKobayashi and @kantasv.

- Korean by @keispace, @jiyongp, @jooyunghan, and @namhyung.

- Spanish by @deavid.

- Ukrainian by @git-user-cpp, @yaremam and @reta.

Use the language picker in the top-right corner to switch between languages.

Incomplete Translations

There is a large number of in-progress translations. We link to the most recently updated translations:

- Arabic by @younies

- Bengali by @raselmandol.

- French by @KookaS, @vcaen and @AdrienBaudemont.

- German by @Throvn and @ronaldfw.

- Italian by @henrythebuilder and @detro.

The full list of translations with their current status is also available either as of their last update or synced to the latest version of the course.

If you want to help with this effort, please see our instructions for how to get going. Translations are coordinated on the issue tracker.

- This is a good opportunity to thank the volunteers who have contributed to the translations.

- If there are students in the class who speak any of the listed languages, you can encourage them to check out the translated versions and even contribute if they find any issues.

- Highlight that the project is open source and contributions are welcome, not just for translations but for the course content itself.

Using Cargo

When you start reading about Rust, you will soon meet Cargo, the standard tool used in the Rust ecosystem to build and run Rust applications. Here we want to give a brief overview of what Cargo is and how it fits into the wider ecosystem and how it fits into this training.

Installation

Please follow the instructions on https://rustup.rs/.

This will give you the Cargo build tool (cargo) and the Rust compiler

(rustc). You will also get rustup, a command line utility that you can use

to install different compiler versions.

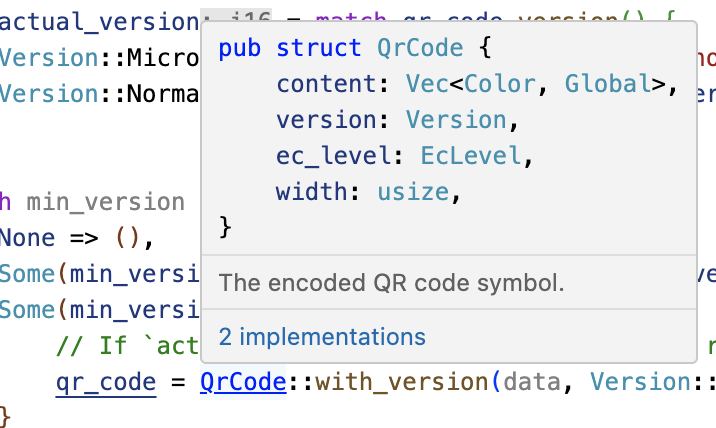

After installing Rust, you should configure your editor or IDE to work with Rust. Most editors do this by talking to rust-analyzer, which provides auto-completion and jump-to-definition functionality for VS Code, Emacs, Vim/Neovim, and many others. There is also a different IDE available called RustRover.

-

On Debian/Ubuntu, you can install

rustupviaapt:sudo apt install rustup -

On macOS, you can use Homebrew to install Rust, but this may provide an outdated version. Therefore, it is recommended to install Rust from the official site.

The Rust Ecosystem

The Rust ecosystem consists of a number of tools, of which the main ones are:

-

rustc: the Rust compiler that turns.rsfiles into binaries and other intermediate formats. -

cargo: the Rust dependency manager and build tool. Cargo knows how to download dependencies, usually hosted on https://crates.io, and it will pass them torustcwhen building your project. Cargo also comes with a built-in test runner which is used to execute unit tests. -

rustup: the Rust toolchain installer and updater. This tool is used to install and updaterustcandcargowhen new versions of Rust are released. In addition,rustupcan also download documentation for the standard library. You can have multiple versions of Rust installed at once andrustupwill let you switch between them as needed.

Key points:

-

Rust has a rapid release schedule with a new release coming out every six weeks. New releases maintain backwards compatibility with old releases — plus they enable new functionality.

-

There are three release channels: “stable”, “beta”, and “nightly”.

-

New features are being tested on “nightly”, “beta” is what becomes “stable” every six weeks.

-

Dependencies can also be resolved from alternative registries, git, folders, and more.

-

Rust also has editions: the current edition is Rust 2024. Previous editions were Rust 2015, Rust 2018 and Rust 2021.

-

The editions are allowed to make backwards incompatible changes to the language.

-

To prevent breaking code, editions are opt-in: you select the edition for your crate via the

Cargo.tomlfile. -

To avoid splitting the ecosystem, Rust compilers can mix code written for different editions.

-

Mention that it is quite rare to ever use the compiler directly not through

cargo(most users never do). -

It might be worth alluding that Cargo itself is an extremely powerful and comprehensive tool. It is capable of many advanced features including but not limited to:

- Project/package structure

- workspaces

- Dev Dependencies and Runtime Dependency management/caching

- build scripting

- global installation

- It is also extensible with sub command plugins as well (such as cargo clippy).

-

Read more from the official Cargo Book

-

Code Samples in This Training

For this training, we will mostly explore the Rust language through examples which can be executed through your browser. This makes the setup much easier and ensures a consistent experience for everyone.

Installing Cargo is still encouraged: it will make it easier for you to do the exercises. On the last day, we will do a larger exercise that shows you how to work with dependencies and for that you need Cargo.

The code blocks in this course are fully interactive:

// Copyright 2022 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { println!("Edit me!"); }

You can use Ctrl + Enter to execute the code when focus is in the text box.

Most code samples are editable like shown above. A few code samples are not editable for various reasons:

-

The embedded playgrounds cannot execute unit tests. Copy-paste the code and open it in the real Playground to demonstrate unit tests.

-

The embedded playgrounds lose their state the moment you navigate away from the page! This is the reason that the students should solve the exercises using a local Rust installation or via the Playground.

Running Code Locally with Cargo

If you want to experiment with the code on your own system, then you will need

to first install Rust. Do this by following the

instructions in the Rust Book. This should give you a working rustc and

cargo. At the time of writing, the latest stable Rust release has these

version numbers:

% rustc --version

rustc 1.69.0 (84c898d65 2023-04-16)

% cargo --version

cargo 1.69.0 (6e9a83356 2023-04-12)

You can use any later version too since Rust maintains backwards compatibility.

With this in place, follow these steps to build a Rust binary from one of the examples in this training:

-

Click the “Copy to clipboard” button on the example you want to copy.

-

Use

cargo new exerciseto create a newexercise/directory for your code:$ cargo new exercise Created binary (application) `exercise` package -

Navigate into

exercise/and usecargo runto build and run your binary:$ cd exercise $ cargo run Compiling exercise v0.1.0 (/home/mgeisler/tmp/exercise) Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.75s Running `target/debug/exercise` Hello, world! -

Replace the boilerplate code in

src/main.rswith your own code. For example, using the example on the previous page, makesrc/main.rslook like// Copyright 2022 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { println!("Edit me!"); } -

Use

cargo runto build and run your updated binary:$ cargo run Compiling exercise v0.1.0 (/home/mgeisler/tmp/exercise) Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.24s Running `target/debug/exercise` Edit me! -

Use

cargo checkto quickly check your project for errors, usecargo buildto compile it without running it. You will find the output intarget/debug/for a normal debug build. Usecargo build --releaseto produce an optimized release build intarget/release/. -

You can add dependencies for your project by editing

Cargo.toml. When you runcargocommands, it will automatically download and compile missing dependencies for you.

Try to encourage the class participants to install Cargo and use a local editor. It will make their life easier since they will have a normal development environment.

Welcome to Day 1

This is the first day of Rust Fundamentals. We will cover a broad range of topics today:

- Basic Rust syntax: variables, scalar and compound types, enums, structs, references, functions, and methods.

- Types and type inference.

- Control flow constructs: loops, conditionals, and so on.

- User-defined types: structs and enums.

Schedule

Including 10 minute breaks, this session should take about 2 hours and 10 minutes. It contains:

| Segment | Duration |

|---|---|

| Welcome | 5 minutes |

| Hello, World | 15 minutes |

| Types and Values | 40 minutes |

| Control Flow Basics | 45 minutes |

Please remind the students that:

- They should ask questions when they get them, don’t save them to the end.

- The class is meant to be interactive and discussions are very much encouraged!

- As an instructor, you should try to keep the discussions relevant, i.e., keep the discussions related to how Rust does things vs. some other language. It can be hard to find the right balance, but err on the side of allowing discussions since they engage people much more than one-way communication.

- The questions will likely mean that we talk about things ahead of the slides.

- This is perfectly okay! Repetition is an important part of learning. Remember that the slides are just a support and you are free to skip them as you like.

The idea for the first day is to show the “basic” things in Rust that should have immediate parallels in other languages. The more advanced parts of Rust come on the subsequent days.

If you’re teaching this in a classroom, this is a good place to go over the schedule. Note that there is an exercise at the end of each segment, followed by a break. Plan to cover the exercise solution after the break. The times listed here are a suggestion in order to keep the course on schedule. Feel free to be flexible and adjust as necessary!

Hello, World

This segment should take about 15 minutes. It contains:

| Slide | Duration |

|---|---|

| What is Rust? | 10 minutes |

| Benefits of Rust | 3 minutes |

| Playground | 2 minutes |

What is Rust?

Rust is a new programming language that had its 1.0 release in 2015:

- Rust is a statically compiled language in a similar role as C++

rustcuses LLVM as its backend.

- Rust supports many

platforms and architectures:

- x86, ARM, WebAssembly, …

- Linux, Mac, Windows, …

- Rust is used for a wide range of devices:

- firmware and boot loaders,

- smart displays,

- mobile phones,

- desktops,

- servers.

Rust fits in the same area as C++:

- High flexibility.

- High level of control.

- Can be scaled down to very constrained devices such as microcontrollers.

- Has no runtime or garbage collection.

- Focuses on reliability and safety without sacrificing performance.

Benefits of Rust

Some unique selling points of Rust:

-

Compile time memory safety - whole classes of memory bugs are prevented at compile time

- No uninitialized variables.

- No double-frees.

- No use-after-free.

- No

NULLpointers. - No forgotten locked mutexes.

- No data races between threads.

- No iterator invalidation.

-

No undefined runtime behavior - what a Rust statement does is never left unspecified

- Array access is bounds checked.

- Integer overflow is defined (panic or wrap-around).

-

Modern language features - as expressive and ergonomic as higher-level languages

- Enums and pattern matching.

- Generics.

- No overhead FFI.

- Zero-cost abstractions.

- Great compiler errors.

- Built-in dependency manager.

- Built-in support for testing.

- Excellent Language Server Protocol support.

Do not spend much time here. All of these points will be covered in more depth later.

Make sure to ask the class which languages they have experience with. Depending on the answer you can highlight different features of Rust:

-

Experience with C or C++: Rust eliminates a whole class of runtime errors via the borrow checker. You get performance like in C and C++, but you don’t have the memory unsafety issues. In addition, you get a modern language with constructs like pattern matching and built-in dependency management.

-

Experience with Java, Go, Python, JavaScript…: You get the same memory safety as in those languages, plus a similar high-level language feeling. In addition you get fast and predictable performance like C and C++ (no garbage collector) as well as access to low-level hardware (should you need it).

Playground

The Rust Playground provides an easy way to run short Rust programs, and is the basis for the examples and exercises in this course. Try running the “hello-world” program it starts with. It comes with a few handy features:

-

Under “Tools”, use the

rustfmtoption to format your code in the “standard” way. -

Rust has two main “profiles” for generating code: Debug (extra runtime checks, less optimization) and Release (fewer runtime checks, lots of optimization). These are accessible under “Debug” at the top.

-

If you’re interested, use “ASM” under “…” to see the generated assembly code.

As students head into the break, encourage them to open up the playground and experiment a little. Encourage them to keep the tab open and try things out during the rest of the course. This is particularly helpful for advanced students who want to know more about Rust’s optimizations or generated assembly.

Types and Values

This segment should take about 40 minutes. It contains:

| Slide | Duration |

|---|---|

| Hello, World | 5 minutes |

| Variables | 5 minutes |

| Values | 5 minutes |

| Arithmetic | 3 minutes |

| Type Inference | 3 minutes |

| Exercise: Fibonacci | 15 minutes |

Hello, World

Let us jump into the simplest possible Rust program, a classic Hello World program:

// Copyright 2024 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { println!("Hello 🌍!"); }

What you see:

- Functions are introduced with

fn. - The

mainfunction is the entry point of the program. - Blocks are delimited by curly braces like in C and C++.

- Statements end with

;. printlnis a macro, indicated by the!in the invocation.- Rust strings are UTF-8 encoded and can contain any Unicode character.

This slide tries to make the students comfortable with Rust code. They will see a ton of it over the next four days so we start small with something familiar.

Key points:

-

Rust is very much like other languages in the C/C++/Java tradition. It is imperative and it doesn’t try to reinvent things unless absolutely necessary.

-

Rust is modern with full support for Unicode.

-

Rust uses macros for situations where you want to have a variable number of arguments (no function overloading).

-

println!is a macro because it needs to handle an arbitrary number of arguments based on the format string, which can’t be done with a regular function. Otherwise it can be treated like a regular function. -

Rust is multi-paradigm. For example, it has powerful object-oriented programming features, and, while it is not a functional language, it includes a range of functional concepts.

Variables

Rust provides type safety via static typing. Variable bindings are made with

let:

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { let x: i32 = 10; println!("x: {x}"); // x = 20; // println!("x: {x}"); }

-

Uncomment the

x = 20to demonstrate that variables are immutable by default. Add themutkeyword to allow changes. -

Warnings are enabled for this slide, such as for unused variables or unnecessary

mut. These are omitted in most slides to avoid distracting warnings. Try removing the mutation but leaving themutkeyword in place. -

The

i32here is the type of the variable. This must be known at compile time, but type inference (covered later) allows the programmer to omit it in many cases.

Values

Here are some basic built-in types, and the syntax for literal values of each type.

| Types | Literals | |

|---|---|---|

| Signed integers | i8, i16, i32, i64, i128, isize | -10, 0, 1_000, 123_i64 |

| Unsigned integers | u8, u16, u32, u64, u128, usize | 0, 123, 10_u16 |

| Floating point numbers | f32, f64 | 3.14, -10.0e20, 2_f32 |

| Unicode scalar values | char | 'a', 'α', '∞' |

| Booleans | bool | true, false |

The types have widths as follows:

iN,uN, andfNare N bits wide,isizeandusizeare the width of a pointer,charis 32 bits wide,boolis 8 bits wide.

There are a few syntaxes that are not shown above:

- All underscores in numbers can be left out, they are for legibility only. So

1_000can be written as1000(or10_00), and123_i64can be written as123i64.

Arithmetic

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn interproduct(a: i32, b: i32, c: i32) -> i32 { return a * b + b * c + c * a; } fn main() { println!("result: {}", interproduct(120, 100, 248)); }

This is the first time we’ve seen a function other than main, but the meaning

should be clear: it takes three integers, and returns an integer. Functions will

be covered in more detail later.

Arithmetic is very similar to other languages, with similar precedence.

What about integer overflow? In C and C++ overflow of signed integers is actually undefined, and might do unknown things at runtime. In Rust, it’s defined.

Change the i32’s to i16 to see an integer overflow, which panics (checked)

in a debug build and wraps in a release build. There are other options, such as

overflowing, saturating, and carrying. These are accessed with method syntax,

e.g., (a * b).saturating_add(b * c).saturating_add(c * a).

In fact, the compiler will detect overflow of constant expressions, which is why the example requires a separate function.

Type Inference

Rust will look at how the variable is used to determine the type:

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn takes_u32(x: u32) { println!("u32: {x}"); } fn takes_i8(y: i8) { println!("i8: {y}"); } fn main() { let x = 10; let y = 20; takes_u32(x); takes_i8(y); // takes_u32(y); }

This slide demonstrates how the Rust compiler infers types based on constraints given by variable declarations and usages.

It is very important to emphasize that variables declared like this are not of some sort of dynamic “any type” that can hold any data. The machine code generated by such declaration is identical to the explicit declaration of a type. The compiler does the job for us and helps us write more concise code.

When nothing constrains the type of an integer literal, Rust defaults to i32.

This sometimes appears as {integer} in error messages. Similarly,

floating-point literals default to f64.

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { let x = 3.14; let y = 20; assert_eq!(x, y); // ERROR: no implementation for `{float} == {integer}` }

Exercise: Fibonacci

The Fibonacci sequence begins with [0, 1]. For n > 1, the next number is the

sum of the previous two.

Write a function fib(n) that calculates the nth Fibonacci number. When will

this function panic?

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn fib(n: u32) -> u32 { if n < 2 { // The base case. return todo!("Implement this"); } else { // The recursive case. return todo!("Implement this"); } } fn main() { let n = 20; println!("fib({n}) = {}", fib(n)); }

- This exercise is a classic introduction to recursion.

- Encourage students to think about the base cases and the recursive step.

- The question “When will this function panic?” is a hint to think about integer overflow. The Fibonacci sequence grows quickly!

- Students might come up with an iterative solution as well, which is a great opportunity to discuss the trade-offs between recursion and iteration (e.g., performance, stack overflow for deep recursion).

Solution

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn fib(n: u32) -> u32 { if n < 2 { return n; } else { return fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2); } } fn main() { let n = 20; println!("fib({n}) = {}", fib(n)); }

We use the return syntax here to return values from the function. Later in the

course, we will see that the last expression in a block is automatically

returned, allowing us to omit the return keyword for a more concise style.

The if condition n < 2 does not need parentheses, which is standard Rust

style.

Panic

The exercise asks when this function will panic. The Fibonacci sequence grows

very rapidly. With u32, the calculated values will overflow the 32-bit integer

limit (4,294,967,295) when n reaches 48.

In Rust, integer arithmetic checks for overflow in debug mode (which is the

default when using cargo run). If an overflow occurs, the program will panic

(crash with an error message). In release mode (cargo run --release),

overflow checks are disabled by default, and the number will wrap around

(modular arithmetic), producing incorrect results.

- Walk through the solution step-by-step.

- Explain the recursive calls and how they lead to the final result.

- Discuss the integer overflow issue. With

u32, the function will panic fornaround 47. You can demonstrate this by changing the input tomain. - Show an iterative solution as an alternative and compare its performance and memory usage with the recursive one. An iterative solution will be much more efficient.

More to Explore

For a more advanced discussion, you can introduce memoization or dynamic programming to optimize the recursive Fibonacci calculation, although this is beyond the scope of the current topic.

Control Flow Basics

This segment should take about 45 minutes. It contains:

| Slide | Duration |

|---|---|

| Blocks and Scopes | 5 minutes |

| if Expressions | 4 minutes |

| match Expressions | 5 minutes |

| Loops | 5 minutes |

| break and continue | 4 minutes |

| Functions | 3 minutes |

| Macros | 2 minutes |

| Exercise: Collatz Sequence | 15 minutes |

-

We will now cover the many kinds of flow control found in Rust.

-

Most of this will be very familiar to what you have seen in other programming languages.

Blocks and Scopes

- A block in Rust contains a sequence of expressions, enclosed by braces

{}. - The final expression of a block determines the value and type of the whole block.

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { let z = 13; let x = { let y = 10; dbg!(y); z - y }; dbg!(x); // dbg!(y); }

If the last expression ends with ;, then the resulting value and type is ().

A variable’s scope is limited to the enclosing block.

-

You can explain that dbg! is a Rust macro that prints and returns the value of a given expression for quick and dirty debugging.

-

You can show how the value of the block changes by changing the last line in the block. For instance, adding/removing a semicolon or using a

return. -

Demonstrate that attempting to access

youtside of its scope won’t compile. -

Values are effectively “deallocated” when they go out of their scope, even if their data on the stack is still there.

if expressions

You use

if expressions

exactly like if statements in other languages:

// Copyright 2024 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { let x = 10; if x == 0 { println!("zero!"); } else if x < 100 { println!("biggish"); } else { println!("huge"); } }

In addition, you can use if as an expression. The last expression of each

block becomes the value of the if expression:

// Copyright 2024 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { let x = 10; let size = if x < 20 { "small" } else { "large" }; println!("number size: {}", size); }

Because if is an expression and must have a particular type, both of its

branch blocks must have the same type. Show what happens if you add ; after

"small" in the second example.

An if expression should be used in the same way as the other expressions. For

example, when it is used in a let statement, the statement must be terminated

with a ; as well. Remove the ; before println! to see the compiler error.

match Expressions

match can be used to check a value against one or more options:

// Copyright 2024 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { let val = 1; match val { 1 => println!("one"), 10 => println!("ten"), 100 => println!("one hundred"), _ => { println!("something else"); } } }

Like if expressions, match can also return a value;

// Copyright 2024 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { let flag = true; let val = match flag { true => 1, false => 0, }; println!("The value of {flag} is {val}"); }

-

matcharms are evaluated from top to bottom, and the first one that matches has its corresponding body executed. -

There is no fall-through between cases the way that

switchworks in other languages. -

The body of a

matcharm can be a single expression or a block. Technically this is the same thing, since blocks are also expressions, but students may not fully understand that symmetry at this point. -

matchexpressions need to be exhaustive, meaning they either need to cover all possible values or they need to have a default case such as_. Exhaustiveness is easiest to demonstrate with enums, but enums haven’t been introduced yet. Instead we demonstrate matching on abool, which is the simplest primitive type. -

This slide introduces

matchwithout talking about pattern matching, giving students a chance to get familiar with the syntax without front-loading too much information. We’ll be talking about pattern matching in more detail tomorrow, so try not to go into too much detail here.

More to Explore

-

To further motivate the usage of

match, you can compare the examples to their equivalents written withif. In the second case, matching on abool, anif {} else {}block is pretty similar. But in the first example that checks multiple cases, amatchexpression can be more concise thanif {} else if {} else if {} else. -

matchalso supports match guards, which allow you to add an arbitrary logical condition that will get evaluated to determine if the match arm should be taken. However talking about match guards requires explaining about pattern matching, which we’re trying to avoid on this slide.

Loops

There are three looping keywords in Rust: while, loop, and for:

while

The

while keyword

works much like in other languages, executing the loop body as long as the

condition is true.

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { let mut x = 200; while x >= 10 { x = x / 2; } dbg!(x); }

for

The for loop iterates over

ranges of values or the items in a collection:

// Copyright 2024 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { for x in 1..5 { dbg!(x); } for elem in [2, 4, 8, 16, 32] { dbg!(elem); } }

- Under the hood

forloops use a concept called “iterators” to handle iterating over different kinds of ranges/collections. Iterators will be discussed in more detail later. - Note that the first

forloop only iterates to4. Show the1..=5syntax for an inclusive range.

loop

The loop statement just

loops forever, until a break.

// Copyright 2024 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { let mut i = 0; loop { i += 1; dbg!(i); if i > 100 { break; } } }

- The

loopstatement works like awhile trueloop. Use it for things like servers that will serve connections forever.

break and continue

If you want to immediately start the next iteration use

continue.

If you want to exit any kind of loop early, use

break.

With loop, this can take an optional expression that becomes the value of the

loop expression.

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { let mut i = 0; loop { i += 1; if i > 5 { break; } if i % 2 == 0 { continue; } dbg!(i); } }

Note that loop is the only looping construct that can return a non-trivial

value. This is because it’s guaranteed to only return at a break statement

(unlike while and for loops, which can also return when the condition

fails).

Labels

Both continue and break can optionally take a label argument that is used to

break out of nested loops:

// Copyright 2024 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { let s = [[5, 6, 7], [8, 9, 10], [21, 15, 32]]; let mut elements_searched = 0; let target_value = 10; 'outer: for i in 0..=2 { for j in 0..=2 { elements_searched += 1; if s[i][j] == target_value { break 'outer; } } } dbg!(elements_searched); }

- Labeled break also works on arbitrary blocks, e.g.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // Copyright 2024 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 'label: { break 'label; println!("This line gets skipped"); } }

Functions

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn gcd(a: u32, b: u32) -> u32 { if b > 0 { gcd(b, a % b) } else { a } } fn main() { dbg!(gcd(143, 52)); }

- Declaration parameters are followed by a type (the reverse of some programming languages), then a return type.

- The last expression in a function body (or any block) becomes the return

value. Simply omit the

;at the end of the expression. Thereturnkeyword can be used for early return, but the “bare value” form is idiomatic at the end of a function (refactorgcdto use areturn). - Some functions have no return value, and return the ‘unit type’,

(). The compiler will infer this if the return type is omitted. - Overloading is not supported – each function has a single implementation.

- Always takes a fixed number of parameters. Default arguments are not supported. Macros can be used to support variadic functions.

- Always takes a single set of parameter types. These types can be generic, which will be covered later.

Macros

Macros are expanded into Rust code during compilation, and can take a variable

number of arguments. They are distinguished by a ! at the end. The Rust

standard library includes an assortment of useful macros.

println!(format, ..)prints a line to standard output, applying formatting described instd::fmt.format!(format, ..)works just likeprintln!but returns the result as a string.dbg!(expression)logs the value of the expression and returns it.todo!()marks a bit of code as not-yet-implemented. If executed, it will panic.

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn factorial(n: u32) -> u32 { let mut product = 1; for i in 1..=n { product *= dbg!(i); } product } fn fizzbuzz(n: u32) -> u32 { todo!() } fn main() { let n = 4; println!("{n}! = {}", factorial(n)); }

The takeaway from this section is that these common conveniences exist, and how to use them. Why they are defined as macros, and what they expand to, is not especially critical.

The course does not cover defining macros, but a later section will describe use of derive macros.

More To Explore

There are a number of other useful macros provided by the standard library. Some other examples you can share with students if they want to know more:

assert!and related macros can be used to add assertions to your code. These are used heavily in writing tests.unreachable!is used to mark a branch of control flow that should never be hit.eprintln!allows you to print to stderr.

Exercise: Collatz Sequence

The Collatz Sequence is defined as follows, for an arbitrary n1 greater than zero:

- If ni is 1, then the sequence terminates at ni.

- If ni is even, then ni+1 = ni / 2.

- If ni is odd, then ni+1 = 3 * ni + 1.

For example, beginning with n1 = 3:

- 3 is odd, so n2 = 3 * 3 + 1 = 10;

- 10 is even, so n3 = 10 / 2 = 5;

- 5 is odd, so n4 = 3 * 5 + 1 = 16;

- 16 is even, so n5 = 16 / 2 = 8;

- 8 is even, so n6 = 8 / 2 = 4;

- 4 is even, so n7 = 4 / 2 = 2;

- 2 is even, so n8 = 1; and

- the sequence terminates.

Write a function to calculate the length of the Collatz sequence for a given

initial n.

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 /// Determine the length of the collatz sequence beginning at `n`. fn collatz_length(mut n: i32) -> u32 { todo!("Implement this") } fn main() { println!("Length: {}", collatz_length(11)); // should be 15 }

Solution

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 /// Determine the length of the collatz sequence beginning at `n`. fn collatz_length(mut n: i32) -> u32 { let mut len = 1; while n > 1 { n = if n % 2 == 0 { n / 2 } else { 3 * n + 1 }; len += 1; } len } fn main() { println!("Length: {}", collatz_length(11)); // should be 15 }

This solution demonstrates a few key Rust features:

mutarguments: Thenargument is declared asmut n. This makes the local variablenmutable within the function scope. It does not affect the caller’s value, as integers areCopytypes passed by value.ifexpressions: Rust’sifis an expression, meaning it produces a value. We assign the result of theif/elseblock directly ton. This is more concise than writingn = ...inside each branch.- Implicit return: The function ends with

len(without a semicolon), which is automatically returned.

- Note that

nmust be strictly greater than 0 for the Collatz sequence to be valid. The function signature takesi32, but the problem description implies positive integers. A more robust implementation might useu32or return anOptionorResultto handle invalid inputs (0 or negative numbers), but panic or infinite loops are potential outcomes here ifn <= 0. - The overflow is a potential issue if

ngrows too large, similar to the Fibonacci exercise.

Welcome Back

Including 10 minute breaks, this session should take about 2 hours and 45 minutes. It contains:

| Segment | Duration |

|---|---|

| Tuples and Arrays | 35 minutes |

| References | 55 minutes |

| User-Defined Types | 1 hour |

Tuples and Arrays

This segment should take about 35 minutes. It contains:

| Slide | Duration |

|---|---|

| Arrays | 5 minutes |

| Tuples | 5 minutes |

| Array Iteration | 3 minutes |

| Patterns and Destructuring | 5 minutes |

| Exercise: Nested Arrays | 15 minutes |

- We have seen how primitive types work in Rust. Now it’s time for you to start building new composite types.

Arrays

// Copyright 2024 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { let mut a: [i8; 5] = [5, 4, 3, 2, 1]; a[2] = 0; println!("a: {a:?}"); }

-

Arrays can also be initialized using the shorthand syntax, e.g.

[0; 1024]. This can be useful when you want to initialize all elements to the same value, or if you have a large array that would be hard to initialize manually. -

A value of the array type

[T; N]holdsN(a compile-time constant) elements of the same typeT. Note that the length of the array is part of its type, which means that[u8; 3]and[u8; 4]are considered two different types. Slices, which have a size determined at runtime, are covered later. -

Try accessing an out-of-bounds array element. The compiler is able to determine that the index is unsafe, and will not compile the code:

// Copyright 2024 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { let mut a: [i8; 5] = [5, 4, 3, 2, 1]; a[6] = 0; println!("a: {a:?}"); }

- Array accesses are checked at runtime. Rust optimizes these checks away when possible; meaning if the compiler can prove the access is safe, it removes the runtime check for better performance. They can be avoided using unsafe Rust. The optimization is so good that it’s hard to give an example of runtime checks failing. The following code will compile but panic at runtime:

// Copyright 2024 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn get_index() -> usize { 6 } fn main() { let mut a: [i8; 5] = [5, 4, 3, 2, 1]; a[get_index()] = 0; println!("a: {a:?}"); }

-

We can use literals to assign values to arrays.

-

Arrays are not heap-allocated. They are regular values with a fixed size known at compile time, meaning they go on the stack. This can be different from what students expect if they come from a garbage-collected language, where arrays may be heap allocated by default.

-

There is no way to remove elements from an array, nor add elements to an array. The length of an array is fixed at compile-time, and so its length cannot change at runtime.

Debug Printing

-

The

println!macro asks for the debug implementation with the?format parameter:{}gives the default output,{:?}gives the debug output. Types such as integers and strings implement the default output, but arrays only implement the debug output. This means that we must use debug output here. -

Adding

#, eg{a:#?}, invokes a “pretty printing” format, which can be easier to read.

Tuples

// Copyright 2024 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { let t: (i8, bool) = (7, true); dbg!(t.0); dbg!(t.1); }

-

Like arrays, tuples have a fixed length.

-

Tuples group together values of different types into a compound type.

-

Fields of a tuple can be accessed by the period and the index of the value, e.g.

t.0,t.1. -

The empty tuple

()is referred to as the “unit type” and signifies absence of a return value, akin tovoidin other languages. -

Unlike arrays, tuples cannot be used in a

forloop. This is because aforloop requires all the elements to have the same type, which may not be the case for a tuple. -

There is no way to add or remove elements from a tuple. The number of elements and their types are fixed at compile time and cannot be changed at runtime.

Array Iteration

The for statement supports iterating over arrays (but not tuples).

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { let primes = [2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19]; for prime in primes { for i in 2..prime { assert_ne!(prime % i, 0); } } }

This functionality uses the IntoIterator trait, but we haven’t covered that

yet.

The assert_ne! macro is new here. There are also assert_eq! and assert!

macros. These are always checked, while debug-only variants like debug_assert!

compile to nothing in release builds.

Patterns and Destructuring

Rust supports using pattern matching to destructure a larger value like a tuple into its constituent parts:

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn check_order(tuple: (i32, i32, i32)) -> bool { let (left, middle, right) = tuple; left < middle && middle < right } fn main() { let tuple = (1, 5, 3); println!( "{tuple:?}: {}", if check_order(tuple) { "ordered" } else { "unordered" } ); }

- The patterns used here are “irrefutable”, meaning that the compiler can

statically verify that the value on the right of

=has the same structure as the pattern. - A variable name is an irrefutable pattern that always matches any value, hence

why we can also use

letto declare a single variable. - Rust also supports using patterns in conditionals, allowing for equality comparison and destructuring to happen at the same time. This form of pattern matching will be discussed in more detail later.

- Edit the examples above to show the compiler error when the pattern doesn’t match the value being matched on.

Exercise: Nested Arrays

Arrays can contain other arrays:

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 let array = [[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]];

What is the type of this variable?

Use an array such as the above to write a function transpose that transposes a

matrix (turns rows into columns):

Copy the code below to https://play.rust-lang.org/ and implement the function. This function only operates on 3×3 matrices.

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn transpose(matrix: [[i32; 3]; 3]) -> [[i32; 3]; 3] { todo!() } fn main() { let matrix = [ [101, 102, 103], // <-- the comment makes rustfmt add a newline [201, 202, 203], [301, 302, 303], ]; println!("Original:"); for row in matrix { println!("{row:?}"); } let transposed = transpose(matrix); println!("\nTransposed:"); for row in transposed { println!("{row:?}"); } }

Solution

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn transpose(matrix: [[i32; 3]; 3]) -> [[i32; 3]; 3] { let mut result = [[0; 3]; 3]; for i in 0..3 { for j in 0..3 { result[j][i] = matrix[i][j]; } } result } fn main() { let matrix = [ [101, 102, 103], // <-- the comment makes rustfmt add a newline [201, 202, 203], [301, 302, 303], ]; println!("Original:"); for row in matrix { println!("{row:?}"); } let transposed = transpose(matrix); println!("\nTransposed:"); for row in transposed { println!("{row:?}"); } }

- Array Types: The type

[[i32; 3]; 3]represents an array of size 3, where each element is itself an array of 3i32s. This is how multi-dimensional arrays are typically represented in Rust. - Initialization: We initialize

resultwith zeros ([[0; 3]; 3]) before filling it. Rust requires all variables to be initialized before use; there is no concept of “uninitialized memory” in safe Rust. - Copy Semantics: Arrays of

Copytypes (likei32) are themselvesCopy. When we passmatrixto the function, it is copied by value. Theresultvariable is a new, separate array. - Iteration: We use standard

forloops with ranges (0..3) to iterate over indices. Rust also has powerful iterators, which we will see later, but indexing is straightforward for this matrix transposition.

- Mention that

[i32; 3]is a distinct type from[i32; 4]. Array sizes are part of the type signature. - Ask students what would happen if they tried to return

matrixdirectly after modifying it (if they changed the signature tomut matrix). (Answer: It would work, but it would return a modified copy, leaving the original inmainunchanged).

References

This segment should take about 55 minutes. It contains:

| Slide | Duration |

|---|---|

| Shared References | 10 minutes |

| Exclusive References | 5 minutes |

| Slices | 10 minutes |

| Strings | 10 minutes |

| Reference Validity | 3 minutes |

| Exercise: Geometry | 20 minutes |

Shared References

A reference provides a way to access another value without taking ownership of the value, and is also called “borrowing”. Shared references are read-only, and the referenced data cannot change.

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { let a = 'A'; let b = 'B'; let mut r: &char = &a; dbg!(r); r = &b; dbg!(r); }

A shared reference to a type T has type &T. A reference value is made with

the & operator. The * operator “dereferences” a reference, yielding its

value.

-

References can never be null in Rust, so null checking is not necessary.

-

A reference is said to “borrow” the value it refers to, and this is a good model for students not familiar with pointers: code can use the reference to access the value, but is still “owned” by the original variable. The course will get into more detail on ownership in day 3.

-

References are implemented as pointers, and a key advantage is that they can be much smaller than the thing they point to. Students familiar with C or C++ will recognize references as pointers. Later parts of the course will cover how Rust prevents the memory-safety bugs that come from using raw pointers.

-

Explicit referencing with

&is required, except when invoking methods, where Rust performs automatic referencing and dereferencing. -

Rust will auto-dereference in some cases, in particular when invoking methods (try

r.is_ascii()). There is no need for an->operator like in C++. -

In this example,

ris mutable so that it can be reassigned (r = &b). Note that this re-bindsr, so that it refers to something else. This is different from C++, where assignment to a reference changes the referenced value. -

A shared reference does not allow modifying the value it refers to, even if that value was mutable. Try

*r = 'X'. -

Rust is tracking the lifetimes of all references to ensure they live long enough. Dangling references cannot occur in safe Rust.

-

We will talk more about borrowing and preventing dangling references when we get to ownership.

Exclusive References

Exclusive references, also known as mutable references, allow changing the value

they refer to. They have type &mut T.

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { let mut point = (1, 2); let x_coord = &mut point.0; *x_coord = 20; println!("point: {point:?}"); }

Key points:

-

“Exclusive” means that only this reference can be used to access the value. No other references (shared or exclusive) can exist at the same time, and the referenced value cannot be accessed while the exclusive reference exists. Try making an

&point.0or changingpoint.0whilex_coordis alive. -

Be sure to note the difference between

let mut x_coord: &i32andlet x_coord: &mut i32. The first one is a shared reference that can be bound to different values, while the second is an exclusive reference to a mutable value.

Slices

A slice gives you a view into a larger collection:

// Copyright 2024 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { let a: [i32; 6] = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60]; println!("a: {a:?}"); let s: &[i32] = &a[2..4]; println!("s: {s:?}"); }

- Slices borrow data from the sliced type.

-

We create a slice by borrowing

aand specifying the starting and ending indexes in brackets. -

If the slice starts at index 0, Rust’s range syntax allows us to drop the starting index, meaning that

&a[0..a.len()]and&a[..a.len()]are identical. -

The same is true for the last index, so

&a[2..a.len()]and&a[2..]are identical. -

To easily create a slice of the full array, we can therefore use

&a[..]. -

sis a reference to a slice ofi32s. Notice that the type ofs(&[i32]) no longer mentions the array length. This allows us to perform computation on slices of different sizes. -

Slices always borrow from another object. In this example,

ahas to remain ‘alive’ (in scope) for at least as long as our slice. -

You can’t “grow” a slice once it’s created:

- You can’t append elements of the slice, since it doesn’t own the backing buffer.

- You can’t grow a slice to point to a larger section of the backing buffer. A slice does not have information about the length of the underlying buffer and so you can’t know how large the slice can be grown.

- To get a larger slice you have to go back to the original buffer and create a larger slice from there.

Strings

We can now understand the two string types in Rust:

&stris a slice of UTF-8 encoded bytes, similar to&[u8].Stringis an owned buffer of UTF-8 encoded bytes, similar toVec<T>.

// Copyright 2024 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { let s1: &str = "World"; println!("s1: {s1}"); let mut s2: String = String::from("Hello "); println!("s2: {s2}"); s2.push_str(s1); println!("s2: {s2}"); let s3: &str = &s2[2..9]; println!("s3: {s3}"); }

-

&strintroduces a string slice, which is an immutable reference to UTF-8 encoded string data stored in a block of memory. String literals ("Hello"), are stored in the program’s binary. -

Rust’s

Stringtype is a wrapper around a vector of bytes. As with aVec<T>, it is owned. -

As with many other types

String::from()creates a string from a string literal;String::new()creates a new empty string, to which string data can be added using thepush()andpush_str()methods. -

The

format!()macro is a convenient way to generate an owned string from dynamic values. It accepts the same format specification asprintln!(). -

You can borrow

&strslices fromStringvia&and optionally range selection. If you select a byte range that is not aligned to character boundaries, the expression will panic. Thecharsiterator iterates over characters and is preferred over trying to get character boundaries right. -

For C++ programmers: think of

&strasstd::string_viewfrom C++, but the one that always points to a valid string in memory. RustStringis a rough equivalent ofstd::stringfrom C++ (main difference: it can only contain UTF-8 encoded bytes and will never use a small-string optimization). -

Byte strings literals allow you to create a

&[u8]value directly:// Copyright 2024 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { println!("{:?}", b"abc"); println!("{:?}", &[97, 98, 99]); } -

Raw strings allow you to create a

&strvalue with escapes disabled:r"\n" == "\\n". You can embed double-quotes by using an equal amount of#on either side of the quotes:// Copyright 2024 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { println!(r#"<a href="link.html">link</a>"#); println!("<a href=\"link.html\">link</a>"); }

Reference Validity

Rust enforces a number of rules for references that make them always safe to

use. One rule is that references can never be null, making them safe to use

without null checks. The other rule we’ll look at for now is that references

can’t outlive the data they point to.

// Copyright 2024 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 fn main() { let x_ref = { let x = 10; &x }; dbg!(x_ref); }

-

This slide gets students thinking about references as not simply being pointers, since Rust has different rules for references than other languages.

-

We’ll look at the rest of Rust’s borrowing rules on day 3 when we talk about Rust’s ownership system.

More to Explore

- Rust’s equivalent of nullability is the

Optiontype, which can be used to make any type “nullable” (not just references/pointers). We haven’t yet introduced enums or pattern matching, though, so try not to go into too much detail about this here.

Exercise: Geometry

We will create a few utility functions for 3-dimensional geometry, representing

a point as [f64;3]. It is up to you to determine the function signatures.

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 // Calculate the magnitude of a vector by summing the squares of its coordinates // and taking the square root. Use the `sqrt()` method to calculate the square // root, like `v.sqrt()`. fn magnitude(...) -> f64 { todo!() } // Normalize a vector by calculating its magnitude and dividing all of its // coordinates by that magnitude. fn normalize(...) { todo!() } // Use the following `main` to test your work. fn main() { println!("Magnitude of a unit vector: {}", magnitude(&[0.0, 1.0, 0.0])); let mut v = [1.0, 2.0, 9.0]; println!("Magnitude of {v:?}: {}", magnitude(&v)); normalize(&mut v); println!("Magnitude of {v:?} after normalization: {}", magnitude(&v)); }

Solution

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 /// Calculate the magnitude of the given vector. fn magnitude(vector: &[f64; 3]) -> f64 { let mut mag_squared = 0.0; for coord in vector { mag_squared += coord * coord; } mag_squared.sqrt() } /// Change the magnitude of the vector to 1.0 without changing its direction. fn normalize(vector: &mut [f64; 3]) { let mag = magnitude(vector); for item in vector { *item /= mag; } } fn main() { println!("Magnitude of a unit vector: {}", magnitude(&[0.0, 1.0, 0.0])); let mut v = [1.0, 2.0, 9.0]; println!("Magnitude of {v:?}: {}", magnitude(&v)); normalize(&mut v); println!("Magnitude of {v:?} after normalization: {}", magnitude(&v)); }

-

Note that in

normalizewe were able to do*item /= magto modify each element. This is because we’re iterating using a mutable reference to an array, which causes theforloop to give mutable references to each element. -

It is also possible to take slice references here, e.g.,

fn magnitude(vector: &[f64]) -> f64. This makes the function more general, at the cost of a runtime length check.

User-Defined Types

This segment should take about 1 hour. It contains:

| Slide | Duration |

|---|---|

| Named Structs | 10 minutes |

| Tuple Structs | 10 minutes |

| Enums | 5 minutes |

| Type Aliases | 2 minutes |

| Const | 10 minutes |

| Static | 5 minutes |

| Exercise: Elevator Events | 15 minutes |

Named Structs

Like C and C++, Rust has support for custom structs:

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 struct Person { name: String, age: u8, } fn describe(person: &Person) { println!("{} is {} years old", person.name, person.age); } fn main() { let mut peter = Person { name: String::from("Peter"), age: 27, }; describe(&peter); peter.age = 28; describe(&peter); let name = String::from("Avery"); let age = 39; let avery = Person { name, age }; describe(&avery); }

Key Points:

- Structs work like in C or C++.

- Like in C++, and unlike in C, no typedef is needed to define a type.

- Unlike in C++, there is no inheritance between structs.

- This may be a good time to let people know there are different types of

structs.

- Zero-sized structs (e.g.

struct Foo;) might be used when implementing a trait on some type but don’t have any data that you want to store in the value itself. - The next slide will introduce Tuple structs, used when the field names are not important.

- Zero-sized structs (e.g.

- If you already have variables with the right names, then you can create the struct using a shorthand.

- Struct fields do not support default values. Default values are specified by

implementing the

Defaulttrait which we will cover later.

More to Explore

-

You can also demonstrate the struct update syntax here:

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 let jackie = Person { name: String::from("Jackie"), ..avery }; -

It allows us to copy the majority of the fields from the old struct without having to explicitly type it all out. It must always be the last element.

-

It is mainly used in combination with the

Defaulttrait. We will talk about struct update syntax in more detail on the slide on theDefaulttrait, so we don’t need to talk about it here unless students ask about it.

Tuple Structs

If the field names are unimportant, you can use a tuple struct:

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 struct Point(i32, i32); fn main() { let p = Point(17, 23); println!("({}, {})", p.0, p.1); }

This is often used for single-field wrappers (called newtypes):

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 struct PoundsOfForce(f64); struct Newtons(f64); fn compute_thruster_force() -> PoundsOfForce { todo!("Ask a rocket scientist at NASA") } fn set_thruster_force(force: Newtons) { // ... } fn main() { let force = compute_thruster_force(); set_thruster_force(force); }

- Newtypes are a great way to encode additional information about the value in a

primitive type, for example:

- The number is measured in some units:

Newtonsin the example above. - The value passed some validation when it was created, so you no longer have

to validate it again at every use:

PhoneNumber(String)orOddNumber(u32).

- The number is measured in some units:

- The newtype pattern is covered extensively in the “Idiomatic Rust” module.

- Demonstrate how to add a

f64value to aNewtonstype by accessing the single field in the newtype.- Rust generally avoids implicit conversions, like automatic unwrapping or

using booleans as integers.

- Operator overloading is discussed on Day 2 (Standard Library Traits).

- Rust generally avoids implicit conversions, like automatic unwrapping or

using booleans as integers.

- When a tuple struct has zero fields, the

()can be omitted. The result is a zero-sized type (ZST), of which there is only one value (the name of the type).- This is common for types that implement some behavior but have no data

(imagine a

NullReaderthat implements some reader behavior by always returning EOF).

- This is common for types that implement some behavior but have no data

(imagine a

- The example is a subtle reference to the Mars Climate Orbiter failure.

Enums

The enum keyword allows the creation of a type which has a few different

variants:

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 #[derive(Debug)] enum Direction { Left, Right, } #[derive(Debug)] enum PlayerMove { Pass, // Simple variant Run(Direction), // Tuple variant Teleport { x: u32, y: u32 }, // Struct variant } fn main() { let dir = Direction::Left; let player_move: PlayerMove = PlayerMove::Run(dir); println!("On this turn: {player_move:?}"); }

Key Points:

- Enumerations allow you to collect a set of values under one type.

Directionis a type with variants. There are two values ofDirection:Direction::LeftandDirection::Right.PlayerMoveis a type with three variants. In addition to the payloads, Rust will store a discriminant so that it knows at runtime which variant is in aPlayerMovevalue.- This might be a good time to compare structs and enums:

- In both, you can have a simple version without fields (unit struct) or one with different types of fields (variant payloads).

- You could even implement the different variants of an enum with separate structs but then they wouldn’t be the same type as they would if they were all defined in an enum.

- Rust uses minimal space to store the discriminant.

-

If necessary, it stores an integer of the smallest required size

-

If the allowed variant values do not cover all bit patterns, it will use invalid bit patterns to encode the discriminant (the “niche optimization”). For example,

Option<&u8>stores either a pointer to an integer orNULLfor theNonevariant. -

You can control the discriminant if needed (e.g., for compatibility with C):

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 #[repr(u32)] enum Bar { A, // 0 B = 10000, C, // 10001 } fn main() { println!("A: {}", Bar::A as u32); println!("B: {}", Bar::B as u32); println!("C: {}", Bar::C as u32); }Without

repr, the discriminant type takes 2 bytes, because 10001 fits 2 bytes.

-

More to Explore

Rust has several optimizations it can employ to make enums take up less space.

-

Null pointer optimization: For some types, Rust guarantees that

size_of::<T>()equalssize_of::<Option<T>>().Example code if you want to show how the bitwise representation may look like in practice. It’s important to note that the compiler provides no guarantees regarding this representation, therefore this is totally unsafe.

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 use std::mem::transmute; macro_rules! dbg_bits { ($e:expr, $bit_type:ty) => { println!("- {}: {:#x}", stringify!($e), transmute::<_, $bit_type>($e)); }; } fn main() { unsafe { println!("bool:"); dbg_bits!(false, u8); dbg_bits!(true, u8); println!("Option<bool>:"); dbg_bits!(None::<bool>, u8); dbg_bits!(Some(false), u8); dbg_bits!(Some(true), u8); println!("Option<Option<bool>>:"); dbg_bits!(Some(Some(false)), u8); dbg_bits!(Some(Some(true)), u8); dbg_bits!(Some(None::<bool>), u8); dbg_bits!(None::<Option<bool>>, u8); println!("Option<&i32>:"); dbg_bits!(None::<&i32>, usize); dbg_bits!(Some(&0i32), usize); } }

Type Aliases

A type alias creates a name for another type. The two types can be used interchangeably.

// Copyright 2023 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 enum CarryableConcreteItem { Left, Right, } type Item = CarryableConcreteItem; // Aliases are more useful with long, complex types: use std::cell::RefCell; use std::sync::{Arc, RwLock}; type PlayerInventory = RwLock<Vec<Arc<RefCell<Item>>>>;

-

A newtype is often a better alternative since it creates a distinct type. Prefer

struct InventoryCount(usize)totype InventoryCount = usize. -

C programmers will recognize this as similar to a

typedef.

const

Constants are evaluated at compile time and their values are inlined wherever they are used:

// Copyright 2024 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 const DIGEST_SIZE: usize = 3; const FILL_VALUE: u8 = calculate_fill_value(); const fn calculate_fill_value() -> u8 { if DIGEST_SIZE < 10 { 42 } else { 13 } } fn compute_digest(text: &str) -> [u8; DIGEST_SIZE] { let mut digest = [FILL_VALUE; DIGEST_SIZE]; for (idx, &b) in text.as_bytes().iter().enumerate() { digest[idx % DIGEST_SIZE] = digest[idx % DIGEST_SIZE].wrapping_add(b); } digest } fn main() { let digest = compute_digest("Hello"); println!("digest: {digest:?}"); }

Only functions marked const can be called at compile time to generate const

values. const functions can however be called at runtime.

- Mention that

constbehaves semantically similar to C++’sconstexpr

static

Static variables will live during the whole execution of the program, and therefore will not move:

// Copyright 2024 Google LLC // SPDX-License-Identifier: Apache-2.0 static BANNER: &str = "Welcome to RustOS 3.14"; fn main() { println!("{BANNER}"); }

As noted in the Rust RFC Book, these are not inlined upon use and have an

actual associated memory location. This is useful for unsafe and embedded code,

and the variable lives through the entirety of the program execution. When a

globally-scoped value does not have a reason to need object identity, const is

generally preferred.

staticis similar to mutable global variables in C++.staticprovides object identity: an address in memory and state as required by types with interior mutability such asMutex<T>.

More to Explore

Because static variables are accessible from any thread, they must be Sync.

Interior mutability is possible through a

Mutex, atomic or

similar.

It is common to use OnceLock in a static as a way to support initialization on

first use. OnceCell is not Sync and thus cannot be used in this context.

Thread-local data can be created with the macro std::thread_local.

Exercise: Elevator Events

We will create a data structure to represent an event in an elevator control

system. It is up to you to define the types and functions to construct various

events. Use #[derive(Debug)] to allow the types to be formatted with {:?}.

This exercise only requires creating and populating data structures so that

main runs without errors. The next part of the course will cover getting data

out of these structures.